PHENOMENALITY: *naturalistic*

MYTHICITY: (1) *good, * (2) *fair*

FRYEAN MYTHOS: *irony*

CAMPBELLIAN FUNCTIONS: *psychological, sociological*

(SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS)

The tragic emotion, in fact, is a face looking two ways, towards terror and towards pity, both of which are phases of it. You see I use the word ARREST. I mean that the tragic emotion is static. Or rather the dramatic emotion is. The feelings excited by improper art are kinetic, desire or loathing. Desire urges us to possess, to go to something; loathing urges us to abandon, to go from something. The arts which excite them, pornographical or didactic, are therefore improper arts. The esthetic emotion (I used the general term) is therefore static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing.-- James Joyce, PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN.

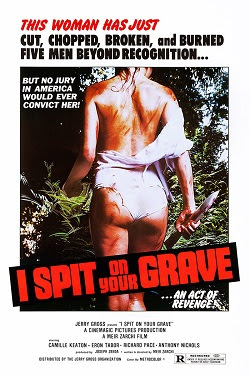

Of the many questions engendered from Meir Zarchi's seminal "rape-and-revenge" saga, the one that first concerns me here is, "is it horror?" My short answer is that GRAVE belongs to the subcategory of naturalistic horror. However, the regular tropes of even naturalistic horror-films are subjected to an intense re-evaluation that gives Zarchi's work the distanced detachment one often finds in serious art-movies-- or in Joyce's above claim that what he calls "the esthetic emotion."

The plot of the original 1978 film is so simple as to resemble a schematic. City woman Jennifer Hills (Camille Keaton) rents a cottage in the wilds of Connecticut, planning to write her first novel. Four locals take note of her good looks. One, Matthew, suffers from mental retardation, but the other three-- Stanley, Andy and Johnny-- bully him into joining their plan to rape Jennifer. The retarded man withholds himself from the assaults on Jennifer for a time, but after seeing her repeatedly turned into a sex object, he joins in. After leaving Jennifer in her rented cottage beaten and abused, the three principal rapists tell Matthew to kill Jennifer off. He fails to do so, and some time later, she retaliates by killing all four of them, often by explicitly gory methods.

(Side-note: before writing this essay, I changed my trope "bizarre crimes" to "bizarre crimes and crimefighting." Like a handful of other films reviewed here, at times the person responding to a mundane crime is the one who comes up with a remarkable counter-measure.)

Zarchi, as I said, assumes an Olympian perspective at all times, whether his camera's surveying the apparent peacefulness of a forest glade or the sight of Jennifer being repeated beaten and ravished. To say the least, this is not the way most films approach the subject of rape, which is often used simply to drive the narrative to levels of new excitement. Zarchi's camera is never excited, even when the viewer sees the culmination of his expectations-- partly because Zarchi delays the reaction so greatly. After Jennifer executes Matthew and hides his body, she suckers Johnny into thinking she really liked the rough stuff, and seduces him until he's totally lowered his guard and leaves himself open to her most "colorful" revenge. After all four men are dead, Zarchi ends the film with Jennifer driving the men's speedboat across a lake, her face strangely bereft of all affect, even satisfaction.

While much criticism of the film has centered on the debate about the way women are represented in cinema, my reason for giving the film a "good" rating has more to do with Zarchi's opposition between the moneyed denizens of the big city and the subsistence-level inhabitants of the bucolic towns. Zarchi's take on the affect-less mental attitude of the rape-survivor also plays a role in my rating.

Due in part to the continued re-examinations of the 1978 film, both a remake and two sequels were made, sometimes with or without Zarchi's participation. DEJA VU is a direct sequel to the first film, portraying events over forty years later, with Zarchi once more assuming sole writer-director duties.

Jennifer Hills (Keaton) has fulfilled her desire to become a famous writer thanks to her ordeal. After being exonerated of the crimes of slaying her rapists, she writes a book about it and becomes a rape counselor (though she's never seen plying her profession). She has an adult daughter, Christy (Jamie Bernadette), who may possibly be the offspring of Johnny's seed.

It's not clear what business brings Jennifer and Christy to a restaurant-rendezvous close to the Connecticut wilderness where Jennifer had her ordeal. Whatever the reason, it's a mistake, for some family-members of Jennifer's victims manage to set a trap for Jennifer and succeed in catching Christy as well. The principal assailants-- discounting a few non-active allies-- are Becky, wife of Johnny (who bitterly resents Jennifer having enjoyed her husband before killing him), Herman father of Matthew, and a brother of Stanley and cousin of Andy. All of them are half-insane and willing to slaughter both women for revenge, but only after inflicting on Jennifer a "Tom and Jerry" chase.

One can see Zarchi trying to capture the Olympian view of his original work, but he's only intermittently successful, and more often he seems to be channeling the comic grand opera of Tobe Hooper instead. Zarchi does make a valiant attempt to keep the viewer guessing-- I for one (remember SPOILERS?) did not guess that Becky would actually succeed in killing off Jennifer. After the death of the original mistress of vengeance, Christy too is subjected to many of the same violence and humiliations suffered by her mother, to say nothing of the shock of finding her mother's murdered corpse.

There are some interesting psychological permutations here. Christy has been a fashion model since an early age, meaning that on some level she's been "selling" her sexuality in a way analogous to what the rubes of the first film think of big-city women. Becky's evil clan is also full of culture-envy about city-folk, with Kevin in particular projecting his own psyche as he claims Jennifer was turned on by her killings. But Zarchi tries to stretch the material out far beyond its meager capacity. Herman, playing an analogue to Matthew in that he's egged on into the others' perfidy, has a quasi-religious reaction to all of the violence-- though of course it's too little too late. Becky is among the last to die, but I must admit Zarchi found an interesting way to off her as well.

The film's 148 minutes long, nearly an hour longer than the original GRAVE. Maybe Zarchi felt this was likely to be his only chance to top himself. He didn't succeed, but I can think of far worse attempts to one-up a famous flick (like, say, all the Disney STAR WARS sequels).

No comments:

Post a Comment