PHENOMENALITY: *marvelous*

MYTHICITY: *fair*

FRYEAN MYTHOS: *adventure*

CAMPBELLIAN FUNCTION: *cosmological, psychological*

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

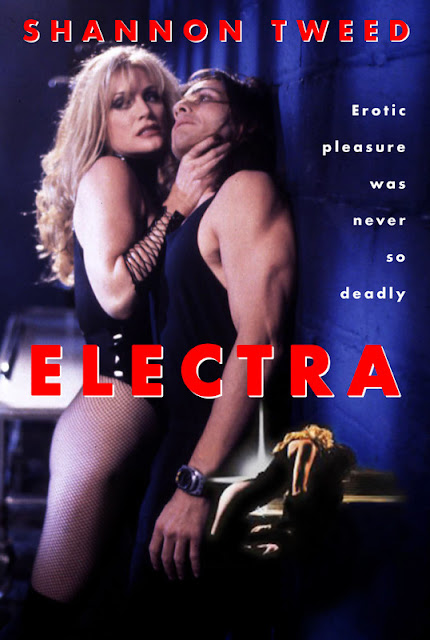

In the 2000s producer Ashok Amritaj broke into the big time with a number of high-profile projects, some of which were superhero-adjacent properties like the GHOST RIDER films and the first MACHETE. But his first real such project-- technically a "super-villain" film-- is this DTV film ELECTRA (that is, if one leaves out an Asian-made ninja film).

Most of the DTV films Amritaj made in the nineties are predictable formula outings, like the NIGHT EYES series of erotic thrillers. ELECTRA, though, is an ambitious genre mashup, quite as if its creators-- writers Lou Aguilar and Damian Lau and director Julian Grant, none of whom had a ton of notable credits-- were seeking to meld the Oedipal drama of Eugene O'Neil with the trash-culture aesthetics of Quentin Tarantino. (In one brief scene between two guards, one of them quotes the "quarter-pounder" line from PULP FICTION before both of them get taken out.) Unlike any work from Tarantino, ELECTRA is an awkward mix of clever ideas and dopey executions, though it's no less entertaining for all that.

Like a lot of regular erotic thrillers, this one starts in a strip club, where in theory women are objectified for lustful males. But one stripper uses her sex to lure a patron to his death in the clutches of her patron, madman Marcus Roach (Sten Eirik). The patron lasts only long enough for Roach's lapdog scientist Bartholomew to inject the fellow with an experimental serum. Things don't go well; the innocent pawn becomes super-strong and bats around his guards for a second or two-- and then he explodes. Roach is terribly disappointed. He's been stuck in a wheelchair for years thanks to a lab accident, and he hoped Bartholomew's serum would cure his affliction. Roach is so broken up that he threatens to let his sexy, martial-arts henchwomen-- all decked out in short-shorts, thigh-high boots and vinyl jackets-- to put the lapdog down.

Bartholomew then reveals that all of his research into a strength-enhancing formula came from a late colleague, one Duncan. Though Duncan is dead, Bartholomew believes that Duncan's son Billy (Joe Tab) not only knows the formula, he's been taking the real serum with no ill effects since childhood. Though both Billy's parents are gone, Doctor Duncan remarried Lorna (Shannon Tweed), the owner of a farm in upstate New York. So Roach lets Bartholomew live, though not without the usual threats, before the villain and his private army proceed to check out Lorna's farm.

The viewer gets a more intimate surveillance of the setup. Billy is a healthy young fellow, but though he dates Mary Anne (Katie Griffin), a local girl his own age, it's risky for him to have unprotected sex with her, since he might transmit the serum to her through his bodily fluids. However, the serum doesn't just enhance Billy's strength, but his sex-drive as well-- and that means that he's got a little thing for his sexy stepmother. Lorna for her part doesn't need serum to make her lust after her hunky son. Though she's being courted by a fellow her own age-- in fact, by Mary Anne's maybe-divorced father, thus jacking up the Oedipal factor up even more-- Lorna's clearly "holding out for a hero." The two of them do make a few desultory attempts to keep things on a normal mom/son level, but Mary Anne knows that Lorna's urges are less than maternal. More, Billy plans to leave for college soon, making Lorna even more forlorn.

Roach sends his goons and his "doll squad" to abduct Billy and Lorna, in the process managing to kill Mary Anne's dad. Billy, being a chemically induced superman, fights off the thugs, but Lorna is captured and taken to Roach's lab.

I said before that this was a super-villain film, but Roach is not the star of this show. Roach has watched enough Ibsen and O'Neill to recognize buried lusts when he sees them. He decides that his best chance to get a viable sample of the formula in Billy's veins is to force him to have sex with a female pawn-- a Frankenstein fraulein of sorts-- and get the serum dispersed into his own body by sexual congress. Roach brainwashes Lorna so that she will lure Billy-- and Mary Anne for good measure-- into his clutches, with Lorna's reward being her hunky stepson. Initially Roach tests captive Billy's resolve by having his two goon-girls try to sex him up, but Billy manages to keep things cool. This gambit proves to be a set-up for the real attack, where Lorna claims to be faking sex with Billy to fool Roach. Billy can't entirely restrain his fundamental lust for his "mom," and because he can't, he creates in her a super-being like himself. Roach provides Lorna with a slinky black cat-suit, and she takes the name "Electra" for no reason.

However, before Mary Anne was captured, Billy slipped her a dose of the enhancing-serum, and she uses it on herself to become a second super-woman. She creams the two goon-girls and then goes after her real enemy. Electra wins their bout, though the serum saves the good girl's life. Electra and Billy engage in an overly short battle and virtue wins out over vice.

I give the actors props for trying as hard as possible to play this concept straight, with the possible exception of the "catfight" scene, where Tweed and Griffin get a little wacky in their death-duel. Nevertheless, getting powers from a spider-bite seems positively sober in comparison to the notion of super-beings passing on their powers through sexual intercourse, so there's no getting away from the risibility factor here. The attire of the goon-girls adds to the lunacy in that it suggests dominance-gear, and one of the girls has an early fight with Billy in which she tosses out lines like, "Don't pass out on me now, pretty boy; I'm not so easily satisfied!" Of course there's a school of thought that sees all costumed characters as incarnations of combined lust and power no matter how family-friendly their adventures might be. It's possible that the makers of ELECTRA were having fun with that idea here, while of course offering the "erotic thriller" crowd all their favorite tropes-- including lots of skin-shots of Shannon Tweed, who had become famous for such fare by the time she made this movie. Yet I would have to say that, even if one can't take ELECTRA seriously, it diverges from the majority of soft-core erotica in that the female characters aren't depending on manipulating men with sex, since they're as physically formidable as they are sexy.

The name Lorna chooses as her super-villain sobriquet is a bit puzzling. If she's a predatory stepmother desiring to pattern herself after a Greek myth-figure, why wouldn't she call herself "Phaedra?" There's one minute in which Electra hurls a bolt of electricity from her hand to stun Billy-- which of course makes no sense in terms of what the serum can do-- but I suspect this extra power was just as a throwaway notion. The Greek Electra was most famous for seeking to avenge the murder of her father Agamemnon by both her mother Clytemnestra and the queen's younger lover. This would seem to put her more on the side of the angels, except that she manipulates her younger brother Orestes into doing her dirty work, which includes the direct slaying of his birth mother to avenge his father. And that's rather close to the denouement of ELECTRA, though unlike Orestes, Billy Duncan gets to make it with his pseudo-mom before he kills her.