PHENOMENALITY: *marvelous*

MYTHICITY: *good*

FRYEAN MYTHOS: *adventure*

CAMPBELLIAN FUNCTION: *metaphysical, psychological*

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

Previous to this post I've given a "good" mythicity rating only to one other sixties peplum, FURY OF ACHILLES, which was a condensation of Homer's ILIAD. This 1964 Hercules film has no such indirect pedigree, and for many it will seem to follow the same template as a dozen others of its kind: strongman hero fights schemers and magicians to keep them from taking possession of a beautiful princess's city. However, for whatever reason, director Alberto di Martino and the two credited screenwriters invested TRIUMPH OF HERCULES with a level of symbol-play that rises to a high level.

One aspect of the Hercules mythology rarely explored in Italian adventure-flicks is his ongoing rivalry with the goddess Hera, whose heaven-ruling husband Zeus played around with a mortal woman and so spawned Hercules-- whose Greek name, "Heracles," has been reliably translated as "glory of Hera." Philip Slater alleges that even though Hercules was not Hera's son, his constant trials at her hands served to test his heroic mettle. In some traditions, the two are finally reconciled when Hercules marries the goddess Hebe, daughter of Hera and Zeus, and by Slater's interpretation an alloform of Hera herself.

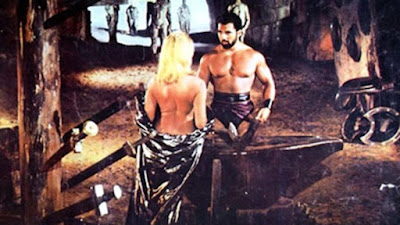

As it happens, when Hercules (Dan Vadis) is first seen in TRIUMPH, he's building a temple to Hera in order to placate her for the "family" quarrel between the two of them (though the film does not dwell on the nature of the quarrel). Evidently he's not far from the city of Mycenae, for when the city's king is slain by his nephew, the usurper Milo (Pierre Cressoy), a runner seeks out Hercules to inform the hero of the coup. Hercules evidently knows Mycenae's princess At'e (Marilu Tolo), but doesn't fall in love with her until he goes to Mycenae to seek justice against Milo. Milo has been close to At'e for years, and Milo tells his fellow schemer (and mother), the sorceress Pasiphae (Moira Orfei), that he thinks he can marry At'e because he's been "like a brother" to her. One might think such filial feeling would be a disadvantage when wooing a woman, but at any rate At'e refuses to believe anything bad about Milo.

She also doesn't ask too many questions when a mysterious septet of golden-skinned, almost invulnerable warriors attacks her citizens. The viewer knows that these golden men are under the control of Milo, because Pasiphae gives Milo a talisman called the Dagger of Jae. Hercules, hearing of the golden men, recognizes that they must be a group of beings he calls "the Hundred-Hands" (loosely related to the Hecatoncheiries of Greek myth). He also knows about the Dagger, which is named for Jae, sister of Hera/Juno (though such a sister does not exist in Greek myth).

Hercules trounces the golden men in their first encounter, so Milo takes a new tack. The usurper knows that Hercules only possesses his supernatural strength by the blessing of Zeus (usually called Jove here). So Milo kidnaps At'e and hoaxers Hercules into attacking an innocent man and killing him. Zeus curses Hercules to lose his strength, and then Milo threatens to slay both hero and princess with a diabolical spike-trap. But while mortal-ized Hercules struggles with the trap, he prays to Zeus to spare At'e and let Hercules die. Zeus gives his son a "like" by restoring his strength, enabling the hero to break free and kick some ass. Milo, with At'e in tow, flees to the caves of Pasiphae, and once more the usurper summons the golden men. During the golden men's battle with Hercules Milo is killed. The bereaved Pasiphae threatens to kill At'e, but the witch meets her doom as well and Hercules unites with At'e to rule Mycenae.

Though this plot is not radically different from a dozen others like it, the writers' use of character-names suggests that they may have been aware of some of the names' more esoteric connotations. The best-known Pasiphae in Greek myth is the wife of King Minos of Crete, and the only way in which she resembles jealous Hera is that in one tale she casts a spell on Minos, causing him to ejaculate serpents when he tries to have sex with other women. That may be the main reason the screenwriters chose the name for their witch-queen.

The movie's Pasiphae is loosely correlated with Hera through the witch's possession of the Dagger of Jae. As noted, there is no Jae in Greek mythology, and Hera's sisters are Hestia and Demeter, respectively the goddesses of the hearth and the harvest. I'm not sure exactly why the writers didn't simply style the weapon "the dagger of Hera (or Juno)," but in antiquity Hera doesn't generally use weapons. So maybe the scripters felt they needed some made-up intermediary figure who represented another aspect of Hera's hostile will. The word "Jae" does sound a bit like that of the Titan "Japetus," who is not directly related to Hera. However, all of the Titans belong to the chthonic order that preceded the rule of the Olympians, as do the beings to whom the golden men are compared, the Hundred-Handed Giants.

Finally, the movie's Pasiphae also emulates Hera in that Pasiphae seeks to have her favored son ascend to a throne. In one Greek narrative, Hera, full of spite for her husband's by-blow, keeps Hercules from the throne of Mycenae by arranging things so that the kingship goes to a man she favors, Eurystheus. Interestingly, the name of the innocent man the Vadis-Hercules kills is "Euristeo," and one of the beings who helps Hera keep Hercules off the throne is a goddess of discord named... At'e.

In many peplum-flicks, the hero in the position of choosing between a glamorous, implicitly-older queen-figure and a more innocent, virginal female. This is not an explicit feature of TRIUMPH. But the way in which Pasiphae attempts to slay Princess At'e is still of interest. She tries to fling At'e off a high cliff, but the princess grabs hold of a ledge. Hercules is on his way to rescue his intended, so Pasiphae's brilliant idea is to morph herself into a duplicate of At'e, and to cling to another ledge. It's Pasiphae's hope that when Hercules appears on the cliff, he'll choose to rescue the wrong princess and let his true love die. The big galoot actually does start to rescue the disguised witch first, but he looks into her eyes and says that "At'e's eyes are clear, like her soul!" Pasiphae, having no good backup plans, falls to her death. What I see happening here, then, is that the screenwriters couldn't entirely resist giving their strongman-hero a choice between older woman and younger woman, even if it was just in a last-minute throwaway scene. (Note; actress Orfei was about thirteen years older than actress Tolo.) I was further tempted to see an identity between Pasiphae and At'e after the fashion of Hera and Hebe, but this isn't as much evidence for this as for the writers' desire to channel the hostility of the Olympian Hera through the made-up figure of a mortal sorceress-- partly because Pasiphae, unlike Hera, could be decisively killed at the climax.